Silicon Catalyst and Qnity, a spin off from Dupont, at the 2026 Chiplet Summit

Insights from SEMI President and CEO Ajit Manocha

Panel Discussion

On-the-Road to a $1 Trillion Industry

Reaching $1 trillion in annual semiconductor sales by 2030 presents both significant challenges and offers compelling opportunities. Demand is accelerating, driven by AI, automotive, data centers, and IoT - but scaling to meet this demand requires massive investments in manufacturing capacity, talent, and R&D.

The global supply chain must become more resilient and geographically diversified, especially amid export control and tariffs. Advanced nodes, chiplets, and new materials promise performance gains but add design and integration complexity. Sustainability is another growing concern, with energy consumption and water usage drawing regulatory and public scrutiny.

Yet, the pathway to $1 trillion is feasible. Public-private partnerships, continued innovation, and strong end-market growth can unlock the next era of expansion. Strategic collaboration across the ecosystem—from startups to foundries—will be essential. Companies that adapt quickly and invest wisely will help shape a more connected, intelligent, and prosperous future for the semiconductor industry.

illustrious speakers included:

Moderator: David French, Board Member, Silicon Catalyst

Panel Members:

Ann Kelleher, Executive VP & GM (retired) Technology Development, at Intel

Ravi Subramanian, Chief Product Management Officer at Synopsys

Ralph Wittig, Corporate Fellow, CVP Head of Research & Advanced Development, AMD

About the Forum

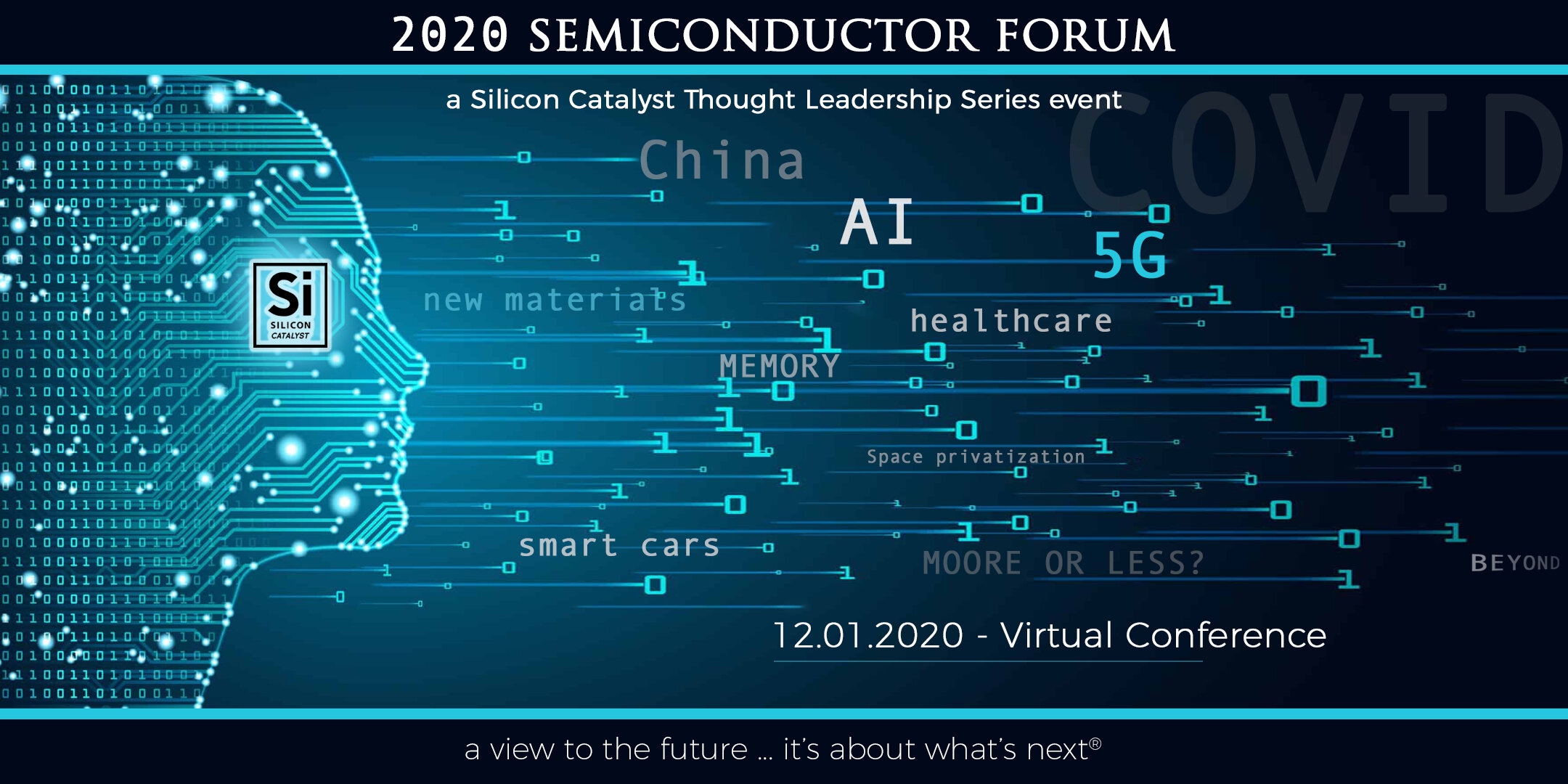

The Silicon Catalyst Semiconductor Industry Forum was launched in 2018. The Forum’s charter is to enable a town-hall like event to discuss the broad impact of semiconductors on our world, beyond the traditional focus on technology, financial reviews and industry business forecasts.

Illuminating the Photonic Innovation Landscape

The photonics industry is at the forefront of technological advancement, driving innovations in telecommunications, healthcare, manufacturing, and beyond. However, as the field evolves, startups face significant challenges, from high development costs, complex testing and packaging solutions and integration.

This webinar will focus on semiconductor applications and explore the key obstacles in the photonics landscape, highlight the innovations needed to unlock new applications, and discuss emerging opportunities for startups looking to make an impact.

Silicon Catalyst and Photon Delta invite you to join industry experts as we dive into the future of photonics and discuss strategies for startup success in this rapidly growing sector.

The webinar moderator is Jorn Smeets Managing Director, Photon Delta North America

Panelists include:

Vikas Gupta, Senior Director of Product Management, Global Foundries

Dr. Armand Niederberger, Executive Director, Stanford Photonics Research Center

Pooya Tadayon, VP of Packaging and Test, Ayar Labs

Martin Vallo, Senior Analyst Photonics, Yole Group

The world we live in is at a major inflection point, as the symbiotic relationship between generative AI and semiconductors will impact society for generations to come. The tremendous advances in semiconductor technology have resulted in an explosion of new applications and business opportunities for artificial intelligence. The resulting development and ubiquitous deployment of AI is driving the need for further semiconductor innovation, in concert with environmental goals. Most importantly, and hopefully in parallel, it will also drive the establishment of guardrails to further improve our AI-centric safety.

Technologists and investors, along with government policy makers, are grappling with the daunting challenges arising from the rapidly evolving development and deployment of artificial intelligence technology. The challenge in front of “all of us” is to maximize the key beneficial aspects of AI, while ensuring the safe use of AI in all aspects of our industries, businesses, our lives and the planet.

With this as the backdrop, Silicon Catalyst held the 2024 Semi Industry Forum at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. The event was entitled: GenAI + Semiconductors + Humanity. Our esteemed panel of experts discussed AI’s technical and business opportunities, as well as the public and private policy initiatives to safely address the challenges ahead.

illustrious speakers included:

Moderator: David French CEO, SigmaSense and Board Member, Silicon Catalyst

Panel Members:

Navin Chaddha, Managing Partner, Mayfield

Chloe Ma, VP of IoT Line of Business / GTM China, Arm

Jay Dawani, CEO and Co-Founder of Lemurian Labs

About the Forum

The Silicon Catalyst Semiconductor Industry Forum was launched in 2018. The Forum’s charter is to enable a town-hall like event to discuss the broad impact of semiconductors on our world, beyond the traditional focus on technology, financial reviews and industry business forecasts.

David French

CEO of SigmaSense, Board of Directors of Silicon Catalyst

Mr. French's career has been built around a very broad set of experiences in virtually all aspects of research, design, manufacturing, marketing and business management within the semiconductor industry. He is perhaps best known for his nearly twenty-year focus on the proliferation of Digital Signal Processing (DSP) technology and solutions in leading successful initiatives at Texas Instruments and later Analog Devices. In addition, he spearheaded the transition of Cirrus Logic's business as its CEO, from a supplier of logic chips into personal computers to become a profitable industry leader in mixed signal audio components and solutions. More recently Mr. French contributed to the financial success of NXP Semiconductors as Executive Vice President of its Mobile and Computing Business Unit and later working on numerous fruitful business divestitures in China. He currently is focused on another application of digital signal processing and high precision sensing technology as the CEO of SigmaSense, LLC, an innovator and leader in AI-enabled touch controllers.

Mr. French has demonstrated a constant emphasis on coaching and development of some of the industry's leading technologists as they have brought their ideas from early formulation to dramatic growth and financial success. With a longstanding presence since 2001 in the China semiconductor marketplace as an investor, advisor, hands on manager and board director, he successfully launched Gaozhan Microelectronics Management Consulting Company and a technology development and incubation center in China, with an early focus on semiconductors for power electronics applications.

Navin Chaddha

Managing Partner, Mayfield

Navin leads Mayfield as Managing Partner. Under his leadership, Mayfield has raised eight U.S. funds and guided over 80 companies topositive outcomes. He has been named a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum and has ranked on the Forbes Midas List of Top 100 Tech Investors sixteen times, including being named in the Top Five in 2020, 2022, 2023, and 2024. Navin’s investments have created over $120 billion in equity value and over 40,000 jobs.

During his venture capital career, Navin invested in over 60 companies, of which 18 have gone public and 27 have been acquired. Navin was one of the earliest Silicon Valley investors to leverage the promise of tech in India. He is Vice Chair of the Stanford Engineering Venture Fund and advisor to Neythri.org. Navin is an active philanthropist who supports education, diversity, equity, inclusion, and food scarcity groups. He serves on the board for Him for Her, a social impact venture aimed at accelerating diversity on corporate boards.

As an entrepreneur, Navin has co-founded or led three startups including VXtreme: a streaming media platform, acquired by Microsoft to become Windows Media; Rivio/CPA.com: a SaaS provider for small businesses, and iBeam Broadcasting (NASDAQ:IBEM): a streaming media content delivery network. Navin holds an MS degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University and a B.Tech degree in electrical engineering from IIT Delhi, where he was honored with the distinguished IIT Alumni Award.

Jay Dawani

CEO and Co-Founder, Lemurian Labs

Jay Dawani is also a Forbes 30 Under 30 Fellow and the Director of Artificial Intelligence at Geometric Energy Corporation (NATO CAGE) and the CEO of Lemurian Labs - a startup he founded that is developing the next generation of autonomy, intelligent process automation, and driver intelligence. Previously he has also been the technology and R&D advisor to Spacebit Capital. He has spent the last three years researching at the frontiers of AI with a focus on reinforcement learning, open-ended learning, deep learning, quantum machine learning, human-machine interaction, multi-agent and complex systems, and artificial general intelligence.

Chloe Ma

VP of IoT Line of Business / GTM China, Arm

Chloe Ma is responsible for market development, ecosystem expansion and overall PL of AIoT, edge computing, robotics and data storage markets. Before joining Arm, Chloe held leadership roles at semiconductor startup SiFive, as well as global semiconductor leaders Intel and Mellanox, delivering significant revenue growth in cloud compute, storage and high-speed cloud networking silicon and module products in the field of cloud infrastructure and hyperscale data centers. Before entering the semiconductor industry, Chloe has 15 years of experience in the field of networking, holding leadership positions in marketing, strategy and software engineering at Cisco, Huawei and Juniper Networks. Chloe holds an MBA from the Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, a master's degree in electrical engineering from the University of Southern California, and a bachelor's degree in Electronics from Peking University, China.

STMicroelectronics' solutions to MEMS Development Challenges

Addressing the challenges early-stage companies face on their quest for research and industrialization options on the way to mass production

This webinar sponsored by Silicon Catalyst, ST and IME provides a look at the challenges many early-stage companies face as they journey through a variety of research and industrialization options on the way to a mass production facility.

Most MEMS and Sensor companies struggle to find a capable industrialization partner that can support their early-stage research, help them develop and transition their unique concept process technology to high-volume production. Not having the right partner results in delays and increased development costs as the design is moved numerous times to various facilities.

1- Introduction: Paul Pickering, Managing Partner, Silicon Catalyst

2- MEMS market research: Pierre Delbos,Technology & Market Analyst at Yole Intelligence

3- ST Lab-in-Fab: Andreja Erbes, PhD, Director of Technology Scouting and R&D Partnerships, STMicroelectronics

4- ST & Silicon Catalyst MEMS Contest Information

5- Q&A Session

SIA Webinar

Hosted by Silicon Catalyst

Encouraging Innovation: The Policies and Partnerships Needed to Support Semiconductor Startups

Dan Armbrust, Co-founder and Director, Silicon Catalyst

Startups are a critical part of the semiconductor ecosystem, and have been since the birth of the industry, driving growth and innovation in the industry and exploring new frontiers of chip technology. Unfortunately, startups in the semiconductor sector face significant challenges and barriers to entry. Creative and ambitious policy solutions and expanded public-private collaboration are needed to help semiconductor startups grow and strengthen. Join SIA and Dan Armbrust from Silicon Catalyst—the world’s only incubator and accelerator for startups focused on semiconductor solutions— for a discussion on the opportunities and challenges facing semiconductor startups, and the actions needed to reinforce and expand this important part of the semiconductor ecosystem.

GSME Global Semiconductor Startup Forum

at the San Jose Convention Center

December 5, 2023 - The first of its kind, Semiconductor startup forum on IC design & manufacturing services, hosted by GSME, to support innovative start-ups, small to mid-size private companies to evaluate, collaborate and discuss the ecosystem. Highlighted by a prominent keynote speaker and industry experts panel, the forum offered an engaging platform to connect, exchange ideas, gain knowledge, and build relationships at the vendor pavilion.

Nick Kepler, COO of Silicon Catalyst, participated in the session, "Industry Trends and Investment Panel"

More details at globalsemiconductorstartupforum.com/our-gallery

Thanks to the author Lewis Carroll, the phrase “wonderland” has been defined as a place that elicits admiration and wonder, to create a place of magical charm. But as we’ve seen and experienced in 2023, in the context of AI, it takes on a more relevant meaning as a place of great opportunity and potentially serious concerns - that generative AI might pose a “civilizational risk”, as recently reported to have been stated in US Congressional hearings by a well known high-tech executive.

This year’s Silicon Catalyst Semiconductor Industry Forum will discuss how the AI era we’ve now entered will impact our industry, our society and most importantly, the world we live in. The panelists will share their thoughts on how best to address some key questions that arise as we look to navigate the years ahead in our new AI wonderland:

The panelists will share their thoughts on how best to address some key questions that arise as we look to navigate the years ahead in our new AI wonderland:

What are the AI technologies that will create new business models and industries?

What are the implications to semiconductor industry success for incumbents & startups?

How do we address the power-hungry AI hyper-scalers’ impact on our energy resources?

What impact will potential government and industry regulations have on innovation?

The live broadcast of this webinar will be moderated by Nitin Dahad, EE Times Correspondent, with his esteemed panelists:

Join illustrious speakers:

Moderator: David French - CEO, SigmaSense and Silicon Catalyst Board Member; ex-NXP, TI, Cirrus Logic

Panel Members:

Deirdre Hanford - Chief Security Officer, Corp Staff, Synopsys; CHIPS Act Semi Working Group

Moshe Gavrielov – Former CEO of Xilinx; Board member of TSMC & NXP

Ivo Bolsens - Senior Vice President, Head Corp Research and Advanced Development, AMD

About the Forum

The Silicon Catalyst Semiconductor Industry Forum was launched in 2018. The Forum’s charter is to enable a town-hall like event to discuss the broad impact of semiconductors on our world, beyond the traditional focus on technology, financial reviews and industry business forecasts.

David French - CEO of SigmaSense, Board of Directors of Silicon Catalyst

Mr. French's career has been built around a very broad set of experiences in virtually all aspects of research, design, manufacturing, marketing and business management within the semiconductor industry. He is perhaps best known for his nearly twenty year focus on the proliferation of Digital Signal Processing (DSP) technology and solutions in leading successful initiatives at Texas Instruments and later Analog Devices. In addition, he spearheaded the transition of Cirrus Logic's business as its CEO, from a supplier of logic chips into personal computers to become a profitable industry leader in mixed signal audio components and solutions. More recently Mr. French contributed to the financial success of NXP Semiconductors as Executive Vice President of its Mobile and Computing Business Unit and later working on numerous fruitful business divestitures in China. He has demonstrated a constant emphasis on coaching and development of some of the industry's leading technologists as they have brought their ideas from early formulation to dramatic growth and financial success.

A recurring theme in his success has grown out of the identification and implementation of fabrication process optimization ideas to drive the achievement of higher levels of product performance at lower cost in communication, audio, media and automotive applications. With a longstanding presence since 2001 in the China semiconductor marketplace as an investor, advisor, hands on manager and board director, he has recently launched Gaozhan Microelectronics Management Consulting Company there. One of his most recent projects has been to introduce a technology development and incubation.

Deirdre Hanford - Chief Security Officer, Corporate Staff, Synopsys

Ms. Hanford serves as Chief Security Officer for Synopsys. In this role, she works collaboratively to safeguard Synopsys. She leads efforts to drive industry awareness and enablement for secure design from software to silicon to support our business in EDA, IP, and Software Integrity. Ms. Hanford previously served as co-general manager of Synopsys’ Design Group, responsible for leading the development and deployment of our physical design, implementation, and analog/mixed signal product lines. She has held a number of positions at Synopsys since joining the company in 1987, including leadership roles in general management, customer engagement, applications engineering, sales, and marketing. Ms. Hanford earned a B.S. Eng (electrical engineering) from Brown University and an M.S.E.E. from UC Berkeley. In September 2022, Ms. Hanford was appointed to the US Department of Commerce’s CHIPS Industrial Advisory Committee.

Ms. Hanford serves on the Board of Directors of Cirrus Logic, Inc. Ms. Hanford currently chairs Synopsys Foundation. She serves on the Engineering Advisory Board for UC Berkeley's College of Engineering. She is co-Chair of Purdue University’s Semiconductor Degrees Leadership Board (SDLB). Ms. Hanford is a board member of NDIA.

Ms. Hanford was named to WomenTech’s 2022 list of Women in Tech Leaders to Watch, VLSI research’s 2017 list of All Stars of the Semiconductor Industry, and National Diversity Council’s 2014 list of Top 50 Most Powerful Women in Technology. In 2001, she was a recipient of the YWCA Tribute to Women and Industry (TWIN) Award and the Marie R. Pistilli Women in EDA Achievement Award.

Moshe Gavrielov - Former CEO of Xilinx; Board Member of TSMC & NXP

Mr. Gavrielov served as president and CEO of Xilinx, Inc. from January 2008 to January 2018 and as director of Xilinx, Inc. from February 2008 to January 2018. Prior to that, he served at Cadence Design Systems, Inc. as executive vice president and general manager of the verification division from April 2005 to November 2007, and CEO of Versity, Ltd. from March 1998 to April 2005. He also served at a variety of executive management positions in LSI Logic Corp. for nearly 10 years, and engineering and engineering management positions in National Semiconductor Corporation and Digital Equipment Corporation. Since 2019, Mr. Gavrielov has served on the board of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSMC), and as of May 2023 he joined the NXP board of directors. In addition, Mr. Gavrielov is the chairman of SiMa Technologies, Inc. and Foretellix, Ltd. Mr. Gavrielov holds a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering and a master's degree in computer science from Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

Dr. Ivo Bolsens - Senior VP, Head Corp Research & Advanced Development, AMD

Ivo Bolsens is the Senior Vice President of AMD, which acquired Xilinx in 2022. Prior to the acquisition, he held the title of Senior Vice President and Chief Technology Officer (CTO), with responsibility for advanced technology development, Xilinx research laboratories (XRL) and Xilinx university program (XUP). The research of his team lead to the industry-leading adoption of 2.5D advanced packaging technology in Xilinx products. Bolsens’ team also spearheaded the introduction of high-level abstraction flows for programming FPGA’s, resulting in the first deployments in data center applications. Additionally, his team was credited for the development of Xilinx’s AI Engine architecture, providing leading edge performance for machine learning applications in the 7nm Versal product family, the first generation of Xilinx’s adaptive compute acceleration platform.

Bolsens came to Xilinx in June 2001 from the Belgium-based research center IMEC, where he was vice president of information and communication systems. His research included the development of knowledge-based verification for VLSI circuits, design of digital signal processing applications, and wireless communication terminals. He also headed the research on design technology for high-level synthesis of DSP hardware, HW/SW co-design and system-on-chip design. Bolsens holds a PhD in applied science and an MSEE from the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium.

Kelly Peng, CEO of Kura Technologies [slide deck]

DP Prakash, co-CEO of Youtopian [slide deck]

Neil Trevett, VP, developer ecosystems at Nvidia [slide deck]

“From AR/VR to Metaverse”

The latest McKinsey research shows that the metaverse has the potential to generate up to $5 trillion in value by 2030. It's an opportunity too big to ignore. [source]

The Metaverse may be the next “Big Thing” of the information age. It has sparked controversies and a bucketload of questions, amongst them: what exactly is the Metaverse; what are its components; how do Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality play into it; what are the potential applications; who will drive its adoption and how will it impact business and social lives?

Silicon Catalyst in conjunction with the Ojo-Yoshida Report assembled a panel of experts to offer insights into the Metaverse and help answer questions on the minds of observers and the potential early adopters. Join our next Thought Leadership Webinar on Wednesday, October 5, 2022, for an engaging focus on the Metaverse and AR/VR.

Join illustrious panelists:

Moderators:

Junko Yoshida, Editor-in-Chief of The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Bolaji Ojo, Publisher & Managing Editor of The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Panelists:

Kelly Peng, CEO of Kura Technologies - Developer of an augmented reality system designed to build the next generation AR optics and display modules

DP Prakash, an IBM and GlobalFoundries veteran and co-CEO of the innovation startup Youtopian

Neil Trevett, vice president, developer ecosystems at Nvidia, and chair of Metaverse Standards Forum

Kelly Peng

CEO, Kura Technologies

Forbes 30 under 30 - Manufacturing & Industry

Kura Technologies awarded Best of CES 2022

Worked on custom frequency-modulated LIDAR with customized mixed-signal ASIC for autonomous vehicles @ UC Berkeley

Lead algorithm developer and organizer of San Francisco Science Exploratorium exhibit on brain-computer interfaces on like-dislike emotion classifier

DP Prakash

co-CEO of the innovation startup Youtopian

Dr. DP Prakash, Co-CEO of Youtopian, is passionate about creating growth engines for leaders in enterprises and education and accelerating the innovation economy. Addressing some of the most complex business problems facing corporations and academia through innovations in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and eXtended Reality (XR), DP leads diverse projects in Metaverse Digital Transformation.

With three decades of Technology experience in the semiconductor industry, DP has led 10 generations of Moore’s law scaling. As a Technologist at IBM and as a former Global Head of Innovation at GlobalFoundries, DP has previously held numerous leadership roles spanning Research, Development and Manufacturing of nanotechnology products.

As a Digital Orchestrator (DOer) of innovation technologies, DP helps leaders in Enterprise and Education stay focused on business outcomes that matter. With deep first-hand experiences and understanding of pain points and a worldwide ecosystem of innovation solution providers, DP provides unbiased guidance for clients to find best fit solutions.

As a recipient of two Outstanding Technical Achievement Awards at IBM in Research and Manufacturing, DP Prakash holds a PhD in Electrical Engineering from University of California, Los Angeles, an MBA with honors from Jack Welch Management Institute, a certificate in Film Producing from UCLA School of Film & Television, a B.Tech in Electronics and Communication Engineering from Indian Institute of Technology, Madras and a certificate on leading Innovation at scale from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

DP likes to do Ashtanga Yoga and practices Hwa Rang Do under the guidance of a living legend, Grandmaster Taejoon Lee. DP lives in New York with his spouse and two children.

Neil Trevett

vice president, developer ecosystems at Nvidia, and chair of Metaverse Standards Forum

Neil Trevett is Vice President of Developer Ecosystems at NVIDIA, where he is responsible for enabling and encouraging advanced applications to use GPU acceleration. Neil is also serving as the elected President of the Khronos Group where he created and chaired the OpenGL ES working group that defined the industry standard for 3D graphics on mobile devices. At Khronos he also chairs the OpenCL working group for portable, parallel heterogeneous computing, helped initiate the WebGL standard that is bringing interactive 3D graphics to the Web and is now working to help formulate standards for vision and neural network inferencing. Previously, as Vice President of 3Dlabs, Neil was at the forefront of the silicon revolution bringing interactive 3D to the PC, and he established the embedded graphics division of 3Dlabs to bring advanced visual processing to a wide-range of non-PC platforms. Neil was elected President for eight consecutive years of the Web3D Consortium dedicated to creating open standards for communicating real-time 3D on the Internet. Neil graduated from Birmingham University in the UK with a First Class Joint Honors B.Sc. in Electronic Engineering and Computer Science and holds several patents in the area of graphics technology.

Moderator: Junko Yoshida

editor-in-chief of the Ojo-Yoshida Report

Junko Yoshida has always been a “roving reporter” in the most literal sense. After logging 11 years of international experience at a Japanese consumer electronics company, Junko pursued a peripatetic journalism career, breaking stories, securing exclusives, and filing incisive analyses from Tokyo, Silicon Valley, Paris, New York, and China. Junko’s contacts and professional experience are global, multicultural, and multilingual. She writes and speaks authoritatively on consumer electronics, automotive, semiconductors, emerging technologies, and intellectual property, with a deep understanding of the business strategies that companies are pursuing to compete on a global scale. During her three decades at EE Times, Junko rose up the ranks from Tokyo correspondent to West Coast bureau chief, European bureau chief, news editor, and editor-in-chief. She earned a reputation as an innovator, shepherding EE Times’ expansion into e-books.

Moderator: Bolaji Ojo

Publisher & Managing Editor the Ojo-Yoshida Report

Veteran business, finance, and technology journalist Bolaji Ojo is a jack-of-all-media but an entrepreneur at heart. “Bola,” a former Bloomberg News reporter and lifelong media innovator, has been a publisher, media executive, business owner, and media market analyst and consultant, working at the nexus of politics, focusing on technology's impact on people & society, and the global supply chain. Over the course of his career, Bolaji has written revealingly - sometimes at his own peril - on topics ranging from the energy market to financial derivatives, the “Nigerian letter scam” and other international fraud cases, politics, policing, and small business. In the late 1980s, he took up the technology beat, covering the electronics supply chain and the interplay among its many players - contract manufacturers, OEMs, design houses, and their network of semiconductor and component sources.

Silicon Catalyst, the world's only incubator focused exclusively on semiconductor solutions, announces the second of a four part thought leadership series in 2022. Silicon Catalyst is pleased to present this series in collaboration with Junko Yoshida and Bolaji Ojo, founders of The Ojo-Yoshida Report. The two world class journalists, who have insightfully reported on technology trends for more than three decades, will moderate an honest and lively dialogue at each webinar.

Each webinar will showcase a Silicon Catalyst portfolio company alongside established leaders in the sectors in which the startups are developing technology solutions.

Now in its eighth year, the Silicon Catalyst incubator has evaluated over 700 startups worldwide and has admitted 85 exciting companies.

thought lead·er/THôt ˈlēdər/noun

a thought leader is someone who, based on their expertise and perspective in an industry, offers unique guidance, inspires innovation and influences others

Silicon Catalyst, the world's only incubator focused exclusively on semiconductor solutions, announces the first of a four part thought leadership series in 2022. Silicon Catalyst is pleased to present this series in collaboration with Junko Yoshida and Bolaji Ojo, founders of The Ojo-Yoshida Report. The two world class journalists, who have insightfully reported on technology trends for more than three decades, will moderate an honest and lively dialogue at each webinar.

Each webinar will showcase a Silicon Catalyst portfolio company alongside established leaders in the sectors in which the startups are developing technology solutions.

Now in its eighth year, the Silicon Catalyst incubator has evaluated over 600 startups worldwide and has admitted more than 45 exciting companies.

Silicon Catalyst in collaboration with the Ojo-Yoshida report presents

“How Safe Are We with Today’s ADAS?”

A Webinar

Talking safety is easy. Claiming safer vehicles is a breeze if you don’t have to back your boasts with proof. SAE levels are product categories, not evidence of any degree of safety.

In this webinar, we share candid insights from leading thinkers and tech developers in a quest to establish clearly where the auto industry stands with sensing technologies and the perception hardware/software stack, as it relates to both driver and pedestrian safety. One of today’s key technology issues is whether carmakers can honestly tell consumers: “We’ve got you covered.” If this isn’t quite so, what is still missing?

Bolaji and Yoshida have decades of experience working at leading publications, covering automotive technology – with safety as their foremost emphasis. Today, The Ojo-Yoshida Report is an independent platform, without favorites or hidden agendas. This inaugural webinar will offer a comprehensive, up-to-the-minute understanding of today’s safety and automation landscape.

Join illustrious panelists:

Moderators:

Junko Yoshida, Editor-in-Chief of The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Bolaji Ojo, Publisher & Managing Editor of The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Panelists:

Matthew Lum, Engineering Program Manager, AAA National

David Aylor, Vice President of Active Safety Testing, The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS)

Jordan Greene, Co-Founder, GM of Automotive & VP of Corporate Development, AEye, Inc.

Chuck Gershman, President & CEO, Owl Autonomous Imaging, Inc

Patrick Denny, Lecturer in Artificial Intelligence and Industry Expert in Automotive Imaging, Univ. of Limerick

Manju Hegde, CEO & Co-founder, Uhnder, Inc.

Matthew Lum

Engineering Program Manager, AAA National

Matthew Lum is an engineering program manager at AAA National with over 6 years of experience in automotive engineering and program management. He oversees full project life cycles across scoping, testing, analysis, and reporting stages. He creates test plans and research methodology, verifies numerical methods for data analysis, allocates project responsibilities, manages timelines, and provides ongoing mentorship to drive overall team development. He also provides reports for stakeholder engagement to include regulatory agencies and media outlets.

David Aylor

vice president of active safety testing, The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS)

David Aylor is vice president of active safety testing at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Mr. Aylor has worked at IIHS since 2004 and has been closely involved with all its testing programs. Most recently, he helped develop the evaluation program for front crash prevention systems. His areas of research include rear impact, low-speed damageability, and crash avoidance technology. Mr. Aylor received a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Virginia.

Jordan Greene

Co-Founder, GM of Automotive & VP of Corporate Development, AEye, inc.

Greene is a leading architect of AEye’s business model, which leverages a highly efficient licensing model and partner strategy to scale manufacturing and distribution. He built out AEye’s partner ecosystem, spearheading partnerships with Global 100 companies and established Tier 1 automotive suppliers, including Continental, Hella, LG Electronics, and Aisin, to drive AEye’s penetration into automotive, industrial and mobility markets. Since 2021, Greene has led AEye’s global automotive group, working closely with Tier 1 auto suppliers and automotive OEMs to bring lidar-enabled safety advancements to market.

Chuck Gershman

President & CEO, Owl Autonomous Imaging, Inc

Mr. Gershman is a Drexel University College of Engineering inductee into the Alumni Circle of Distinction, the highest honor bestowed upon alumni. He has been honored as a finalist for CMP publications (EE Times) prestigious ACE award as High Technology Executive of the Year and was previously named a Top 40 Healthcare Transformer by Medical Marketing & Media for his work on Clinical AI Decision Support for cancer patients. Chuck holds three US patents for his contributions to Microprocessor Architecture. Chuck brings over 30 years of technology and semiconductor industry experience in executive management, marketing, engineering, business development, sales, consulting, and executive advising, including Owl Autonomous Imaging. Mr. Gershman has served as CEO/COO and a Board Director for three companies, he knows what it takes to lead a vision to reality - having led successful exits with acquisitions by Intel and PMC-Sierra.

Patrick Denny

Lecturer in Artificial Intelligence and Industry Expert in Automotive Imaging, Univ. of Limerick

Patrick Denny is a Lecturer in Artificial Intelligence and Industry Expert in Automotive Imaging at the University of Limerick with over 25 years experience in scientific and technological development internationally, 19 of these at a senior level, designing, leading, innovating and consulting on new technologies with multimillion Euro project budgets. His career reflects versatility in developing expertise in diverse areas of science and technology and rapidly making significant contributions in those areas. His knowledge base and experience spans the range from purely academic to market based technology development.

MANJU HEGDE

CEO & CO-FOUDNER, UHNDER, INC.

Manju Hegde is a technology executive, university professor, and serial entrepreneur with more than 25 years of experience in the semiconductor industry. He is the co-founder and CEO of Uhnder, a startup with disruptive digital radar sensing technology that plans to make the world safe for safety – in ADAS and automated mobility applications. Uhnder has formed partnerships with leading automotive manufacturers and suppliers and has announced the launch to production of its first automotive-qualified digital radar-on-chip which will be on the road in production cars in November 2022.

Moderator: Junko Yoshida

editor-in-chief of the Ojo-Yoshida Report

Junko Yoshida has always been a “roving reporter” in the most literal sense. After logging 11 years of international experience at a Japanese consumer electronics company, Junko pursued a peripatetic journalism career, breaking stories, securing exclusives, and filing incisive analyses from Tokyo, Silicon Valley, Paris, New York, and China. Junko’s contacts and professional experience are global, multicultural, and multilingual. She writes and speaks authoritatively on consumer electronics, automotive, semiconductors, emerging technologies, and intellectual property, with a deep understanding of the business strategies that companies are pursuing to compete on a global scale. During her three decades at EE Times, Junko rose up the ranks from Tokyo correspondent to West Coast bureau chief, European bureau chief, news editor, and editor-in-chief. She earned a reputation as an innovator, shepherding EE Times’ expansion into e-books.

Moderator: Bolaji Ojo

Publisher & Managing Editor the Ojo-Yoshida Report

Veteran business, finance, and technology journalist Bolaji Ojo is a jack-of-all-media but an entrepreneur at heart. “Bola,” a former Bloomberg News reporter and lifelong media innovator, has been a publisher, media executive, business owner, and media market analyst and consultant, working at the nexus of politics, focusing on technology's impact on people & society, and the global supply chain. Over the course of his career, Bolaji has written revealingly - sometimes at his own peril - on topics ranging from the energy market to financial derivatives, the “Nigerian letter scam” and other international fraud cases, politics, policing, and small business. In the late 1980s, he took up the technology beat, covering the electronics supply chain and the interplay among its many players - contract manufacturers, OEMs, design houses, and their network of semiconductor and component sources.

SiliconCatalyst.UK and Heriot-Watt University GRID

June 2022

Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing of Semiconductor Startups.

part 2

Silicon Catalyst and Heriot-Watt University GRID delivered the second in the series of the forming ⏰ storming❗norming❓and then performing 🕺 of UK semiconductor startup companies in Edinburgh yesterday to a sold-out event!

These events have been conceived to help new semiconductor founders learn from the ⭐ legends ⭐ of our UK semiconductor industry.

Steve McLaughlin kicked us off with a wonderful insight into the strengths of Heriot-Watt University semiconductor research, entrepreneurship and startup commercialisation.

✅ The ⭐ legend ⭐ Jed Hurwitz Fellow from Analog Devices took us through how bad things "nearly" happen to good people with a deep insight into how he achieved three successful semiconductor start-up exits. Just fantastic.

✅ Then it was all about the team from a very thought provoking Keith Muir Founder and CEO of the brilliant Cytomos backed up by the gregarious Richard Ord from hot new startup Quantum Power Transformation Ltd explaining how their tiny packed revolution in power drive semiconductors is born from years of ingenuity and unique experiences gained by its founder Rob Gwynne.

✅ After a well received break of refreshments, with opportunity to see our exhibitors Synopsys Inc Imagination Technologies 360WORK IC Resources TechWorks NMI & IoTSF, we were given a great introduction to the hugely generous Arm University and Flexible Access program by the very knowledgeable Andrew Pickard & Nivetha Sundararajan.

✅ We then dived into "What problem are you solving" with the ⭐ legend ⭐ Donald McClymont who with the spectacular indie Semiconductor has achieved the holy grail of semiconductor startups by floating on Nasdaq. Wow! This talk makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up on end. Don't miss the video.

✅ Our Silicon Catalyst advisor & In Kind Partner Asen Asenov stormed through how he performed with perfection to create the world leading GSS ltd as a part-time CEO whilst still working as professor University of Glasgow He was followed by the fascinating technology from Brian Gerardot CEO of Atomic Architects on the Heriot-Watt University campus that has the potential to transform feature rich semiconductor manufacturing.

✅ We concluded the presentations with the ⭐ legend ⭐ Pete Hutton Chairman of our In Kind Partner Agile Analog and Cambridge GaN Devices Ltd providing the gold-dust of advice for raising semiconductor startup funding from Angel or VC investors backed up by an early stage & very exciting Heriot-Watt University semiconductor startup @Infinect and the passionate Samuel Rotenberg delivering the first hybrid flat panel antenna for broadband satellite technology.

A huge thank you to all those that attended, contributed and most importantly not forgetting the hard work from Leanne Gunn and the fantastic team at Heriot-Watt University GRID. Great to see David Richardson the instigator of our fruitful collaboration with Heriot-Watt University to help create more exciting semiconductor startups in Scotland.

SiliconCatalyst.UK and TechWorks at Arm, Cambridge, UK

MARCH 2022

Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing of Semiconductor Startups.

Dr. Owen Metters, Williams Advanced Engineering

Seed/Series A Investing in Semiconductor Technologies

Ending Panel

Spring 2022 Advisor Event

March 16, 2022

Invited speaker - Dr. Ron Weissman, board member of the Angel Capital Association and the Band of Angels.

Dr. Weissman will be presenting an abbreviated version of his “Startup Boards Workshop”.

As advisors, your interaction with our Portfolio Company CEOs affords you an opportunity to introduce and reinforce industry “best practices”. Beyond the technical and business development aspects of the startup’s journey to business growth, equally important is the area of corporate governance. This session will also benefit our CEOs as they set up their boards and subsequent meetings.

What to know about Investing in Semiconductor Startups

A webinar

By: Mike Gianfagna

Investing in semiconductor startups is something Silicon Catalyst knows a lot about. During a time when venture funding for chip companies all but disappeared, this remarkable organization built a robust incubator, ecosystem, support infrastructure and funding source. Silicon Catalyst has assembled a top-notch management team and an extensive, world-class advisor network. You can learn more about this remarkable organization here. Silicon Catalyst also has a great track record for putting on compelling events with A-list participants. You can read SemiWiki coverage of their most recent event here. So, when Silicon Catalyst announces a webinar on investing in semiconductor startups, you must take notice.

Chips are Popular Again

It appears the rest of the world is now seeing what Silicon Catalyst saw all along. As stated by Silicon Catalyst:

Following a remarkable year of over 25% year on year growth, the global semiconductor industry is poised to experience strong growth in 2022. World-wide sales for this year are projected to reach in excess of $600 billion in what many are calling the golden era of semiconductors.

Chips are indeed hot again. Another interesting fact courtesy of Silicon Catalyst:

Nuvia is a great example, having taken their first round of money in April 2019 at a post-money valuation of $16 million and being acquired by Qualcomm in March of 2021 for over $1.2 billion.

Examples like this are truly remarkable. They also don’t happen every day. For every home run, there are many more failures. Understanding the trends and developing insight to spot the companies that are correctly leveraging those trends is the focus of the upcoming webinar. As usual, Silicon Catalyst has assembled an all-star cast to discuss these topics. We can all learn a lot from these folks, so I highly recommend you attend this event. More information is coming.

An All-Star Cast Weighs In

Moderated by Cliff Hirsch, Publisher at Semiconductor Times

Panelists:

Rajeev Madhavan - NA, Founder and General Partner, Clear Ventures

Emily Meads - EU, Analyst, Speedinvest

Owen Metters - UK, Investment Manager, Foresight Williams Technology Funds

Dov Moran - Israel, Managing Partner, Grove Venture Capital

And a special presentation by

Junko Yoshida, Editor in Chief, The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Bolaji Ojo, Publisher & Managing Editor, The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Cliff Hirsch

Publisher at Semiconductor Times

Technology executive with 30-year career highlighted by myriad successful sales, marketing and business development initiatives. Unique combination of inspirational leadership, deep strategic insight and tactical “get-it-done” mentality. Vast technology expertise coupled with exceptional business and financial acumen. Massive worldwide professional network developed by cultivating cross-domain relationships with the highest level of integrity, strong work effort, and “no-agenda” problem solving approach. Specialties: Extreme depth and breadth in semiconductors and related technologies, communications, data/telecom network infrastructure, and open source web technology. Analyzed >4,000 private and public companies in the semiconductor & comm/IT space. More information at semiconductortimes.com

Rajeev Madhavan

Founder & General Partner at Clear Ventures

Rajeev Madhavan is a founder and General Partner of Clear, where he focuses on early stage technology investments. Rajeev brings operational skills from founding, building and running (as CEO) two highly successful companies. He has the uncanny ability to deeply understand what entrepreneurs are trying to do, and to steer them onto a successful path. He has been a venture investor in over 35 companies. Rajeev’s notable exits include Apigee (IPO), YuMe (IPO), Virident (acquired), Magma (IPO), Groupon (IPO), VxTel (acquired), LogicVision (IPO) and Ambit (acquired). Prior to founding Clear in 2014, Rajeev founded three successful startups. The most recent, Magma Design Automation, became the 4th largest Electronic Design Automation company in the world under his leadership. Rajeev served as Magma’s Chairman and CEO from when he co-founded the company in 1997 through its acquisition by Synopsys in February 2012 for $580 million.

Emily Meads

Analyst at Speedinvest

Emily is a Physicist by training, holding a Bachelors and Masters in Physics from the University of Bath. She passionately supports Deep Tech companies and the Deep Tech ecosystem, and always strives to give scientific credibility to the VC side of the table. Understanding that key enabling technologies can sometimes get lost behind the walls of academia, she is excited the most by helping founders take their technology out of the lab and into the real world. Before joining Speedinvest, Emily worked for Fraunhofer IZM, as well as a software engineering startup where she first caught the startup bug. She then worked at Spin Up Science where she specifically supported innovators on their Deep Tech commercialization journeys. She draws upon these experiences everyday to sharpen her Deep Tech lens. Her most recent challenge? A Masters in Quantum Computing Technologies, which she is excited to complete to better support the dynamic Quantum ecosystem.

Owen Metters

Investment Manager at Foresight Williams Technology Funds

Dr. Owen Metters is an Investment Manager at Williams Advanced Engineering (WAE). His core focus is sourcing and evaluating new investment opportunities for the Foresight Williams Funds. These funds invest in UK-based deep technology businesses with disruptive and defensible IP and support investee companies by facilitating access to WAE’s engineering team and customer network. Since inception the Foresight Williams Funds have invested £48m into 27 companies operating across a range of sectors. The funds have supported six early-stage, UK-based businesses developing semiconductor devices or tools for the semiconductor industry. Owen has worked at Oxford University Innovation, the technology transfer organization for the University of Oxford, supporting academics in the commercialization of University IP leading to the formation of several successful spin-out companies which have then raised over £20m of VC funding & holds a PhD in Inorganic & Materials Chemistry from Bristol University.

Dov Moran

Managing Partner Grove Ventures

Dov Moran is the Managing Partner of Grove Ventures. He is one of Israel’s most prominent hi-tech leaders, entrepreneurs and investors. Dov is known as a pioneer of several flash memory technologies, most notably as the inventor of the USB flash drive. He was a founder and CEO of M-Systems (NSDQ: FLSH), a world leader in the flash data storage market. Under Dov’s leadership, M-Systems grew to $1B revenue, and was acquired by SanDisk Corp (NSDQ: SNDK) for $1.6B. This still ranks as one of the single biggest acquisitions in Israel. After the sale of M-systems, Dov founded Modu, an innovative company with a revolutionary modular phone concept. Modu’s assets were acquired by Google in 2011 and are the basis for Google’s modular phone Project Ara. Dov has invested in many successful start-ups across multiple sectors, and serves on the boards of RapidAPI, Wiliot, Neuroblade, TriEye and Ramon.Space. He was previously the Chairman of Tower Semiconductors (NASDAQ: TSEM).

Junko Yoshida

Editor in Chief at The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Junko Yoshida has always been a “roving reporter” in the most literal sense. After logging 11 years of international experience at a Japanese consumer electronics company, Junko pursued a peripatetic journalism career, breaking stories, securing exclusives, and filing incisive analyses from Tokyo, Silicon Valley, Paris, New York, and China. Junko’s contacts and professional experience are global, multicultural, and multilingual. She writes and speaks authoritatively on consumer electronics, automotive, semiconductors, emerging technologies, and intellectual property, with a deep understanding of the business strategies that companies are pursuing to compete on a global scale. During her three decades at EE Times, Junko rose up the ranks from Tokyo correspondent to West Coast bureau chief, European bureau chief, news editor, and editor-in-chief. She earned a reputation as an innovator, shepherding EE Times’ expansion into e-books.

Bolaji Ojo

Publisher and Managing Editor at The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Veteran business, finance, and technology journalist Bolaji Ojo is a jack-of-all-media but an entrepreneur at heart. “Bola,” a former Bloomberg News reporter and lifelong media innovator, has been a publisher, media executive, business owner, and media market analyst and consultant, working at the nexus of politics, technology, and the global supply chain. After more than a decade with publications in Africa, Europe, and Asia, Bolaji joined UBM Media in 1999, working as a business editor, managing editor, and editor-in-chief at titles including EE Times, Electronic Buyers’ News, and Electronics Supply & Manufacturing Magazine. He moved to global technology media giant AspenCore along with EE Times and other UBM properties. As AspenCore group publisher and global co-editor-in-chief, he expanded the company’s print, online, and event presence in Asia-Pacific, Europe, and North America.

Semi Industry Forum 4.0:

What Happens Next?

Wednesday December 8, 2021

9am to 11am Pacific

The semiconductor industry has a long history of adapting and evolving to cope with the many challenges that have arisen over the last few decades. For the most part, each of these hurdles have been successfully overcome with breakthrough innovations in technology and business models.

From an evolutionary viewpoint, our industry has moved from being completely vertically integrated to enable competitive differentiation, to today’s global dis-integration of the supply chain, creating whole new semiconductor related industries along the way (electronic design automation, IP, foundry, packaging and semiconductor services) – enabling the ubiquitous and seemingly irreplaceable use of electronic systems in all of the world’s industries and populations.

The semiconductor industry, and society in general, is now at a major inflection point. The globalization of the supply chain, combined with the on-going geo-political turmoil, layered on top of the pandemic, has created a unique set of challenges for our industry, and most importantly, the world at large.

We invite you to join in a dialog with our Forum 4.0 panel as they address key topics, including:

US-China Relationship

Semiconductor Supply Chain Challenges

Regional Government Initiatives with Semiconductor Vendors

WFM / Hybrid Workplace: Impact on Start-ups and Industry Innovation Cycle

Agenda

Semi Industry Update

Mark Edelstone, Chairman of Global Semiconductor Investment Banking, Morgan Stanley

Panel Discussion

Moderated by Don Clark, NY Times Contributing Journalist

Join illustrious speakers:

Janet Collyer - Independent Non-Executive Director, UK Aerospace Technology Institute

Mark Edelstone - Chairman of Global Semiconductor Investment Banking, Morgan Stanley

John Neuffer - President & CEO, Semiconductor Industry Association

Dr. Wally Rhines - President & CEO of Cornami; GSA 2021 Morris Chang Exemplary Leadership award recipient

About the Forum

The Silicon Catalyst Semiconductor Industry Forum series was launched in 2018 with the charter to create a platform for broad-topic dialog among all stakeholders involved in the semiconductor industry value chain. The Forum topics focus on technical and financial aspects of the industry, but more importantly the industry’s societal, geo-political and ecological impact on the world.

Don Clark

Contributing Journalist, New York Times

Don Clark has written about the technology sector for nearly four decades. He spent 23 years at the Wall Street Journal and is currently a freelance contributor to the New York Times. He began his career at the St. Paul Pioneer Press and worked seven years at the San Francisco Chronicle before joining the Journal, where he both wrote and edited stores about the technology sector. He was raised in Pasadena, Calif., and received a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Minnesota and a bachelor’s degree in English from the University of California at Los Angeles. When not engaged in journalism, he is often playing music with his spouse Michele Delattre, including in Shakespeare productions by the Curtain Theatre in Mill Valley.

Janet Collyer

Independent Non-Executive Director, UK Aerospace Technology Institute

Janet Collyer is an Independent Non-Executive Director on the board of the Aerospace Technology Institute (ATI) and Chair of Machine Discovery Limited.

The ATI promotes transformative technology in air transport. It creates the technology strategy for the UK aerospace sector and funds world-class research and development through a £3.9 billion joint government-industry programme. Her international career in the semiconductor industry included Fairchild Semiconductor and most recently Cadence Design Systems Inc. She had various commercial and technology leadership roles including worldwide professional services, sales revenue growth, engineering ecosystems management and semiconductor manufacturing. She is passionate about growing the number of women in technology. Janet earned a Masters degree in Engineering from Girton College, Cambridge University.

Mark Edelstone

Chairman of Global Semiconductor Investment Banking, Morgan Stanley

Mark Edelstone is a Managing Director and Chairman of Global Semiconductor Investment Banking for Morgan Stanley. During his career, he has worked as a portfolio manager, equity research analyst and investment banker, and he has specialized in the semiconductor and technology sectors since 1989. Since then, he has helped many clients to meet their strategic objectives and address their challenges.

During his investment banking career, Mark has advised more than three dozen companies on M&A transactions valued at more than $500 billion, including Xilinx’s $35Bn sale to AMD, Freescale’s $12Bn sale to NXP, Cypress Semiconductor’s $10Bn sale to Infineon, NVIDIA’s $40Bn acquisition of Arm and Analog Device’s $21Bn acquisition of Maxim. Beyond M&A, Mark has led 25 IPOs and has helped dozens of companies to raise more than $150 billion in the debt and equity capital markets. In 2020, Mark was ranked as the second leading M&A banker on the street by Business Insider.

As a research analyst, Mark was selected as an all-star analyst by Institutional Investor magazine for his research coverage of the semiconductor industry for 11 consecutive years. In addition, he was selected five times for the Wall Street Journal’s Stock Picking Award within “The Best on the Street Survey.” During 1999 and 2001, Mark was listed by First Call Corp. as the most-read securities analyst in the world. Prior to his career as a research analyst, Mark founded a money management company that specialized in asset allocation in 1986.

Mark received his undergraduate degree in Political Economics from the University of California and he holds an MBA in Finance, with a concentration in Investments from Golden Gate University in San Francisco. He is a co-founder of the dual-degree Management, Entrepreneurship & Technology Program at the University of California at Berkeley. In addition, he is a Chartered Financial Analyst and a Chartered Market Technician.

John Neuffer

President & CEO Semiconductor Industry Association

John Neuffer has been President and CEO of the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) in Washington, DC since 2015. Mr. Neuffer is responsible for leading the association’s public policy agenda and serving as the primary advocate for maintaining U.S. leadership in semiconductor design, manufacturing, and research. Prior to SIA, he served for seven years as SVP for Global Policy at the Information Technology Industry Council. For the previous two years, he was Deputy Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), preceded by five years as Deputy Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Japan. For nine years before his government service, he was a Senior Research Fellow and Political Analyst with Mitsui Kaijyo Research Institute in Tokyo, where he was a leading commentator on Japanese politics and policy.

Dr. Wally Rhines

President & CEO of Cornami; GSA 2021 Morris Chang Exemplary Leadership award recipient

Dr. Rhines is President and CEO of Cornami, Inc., a fabless software/semiconductor company focused on intelligent computing for fully homomorphic encryption and machine learning. He was previously CEO of Mentor Graphics for 25 years and Chairman of the Board for 17 years. During his tenure at Mentor, revenue nearly quadrupled and market value of the company increased 10X. Prior to joining Mentor Graphics, Dr. Rhines was Executive Vice President, Semiconductor Group, responsible for TI’s worldwide semiconductor business.

Dr. Rhines has served on the boards of Cirrus Logic, QORVO, TriQuint Semiconductor, Global Logic, PTK Corp. and as Chairman of the Electronic Design Automation Consortium (five two-year terms). He is a Lifetime Fellow of the IEEE. Additionally, his experience includes four years on the board of SEMATECH, three years on the board of SEMI-SEMATECH and twenty years on the board of SRC (Semiconductor Research Corporation). Dr. Rhines holds a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering from the University of Michigan, a Master of Science and PhD in materials science and engineering from Stanford University, an MBA from Southern Methodist University and Honorary Doctor of Technology degrees from the University of Florida and Nottingham Trent University.

NPI EAG Webinar 2021

Managing New Product Introduction for First-Pass Success

Successful semiconductor companies marry innovative designs and products to market needs. Key to successful market deployment is the need to map out a production and scaling plan to meet the company’s revenue objectives, especially as the industry is in the midst of significant supply chain disruptions and delays. Thoughtful NPI planning and execution is vital to ultimate success in the market, to ensure the key aspects of quality, scheduling and cost are addressed to meet your revenue objectives.

The webinar will kick-off with a short presentation by Pete Rodriquez, CEO of Silicon Catalyst, detailing his experience with managing the successful launch of new semiconductor products at NXP, Exar and LSI Logic. Pete’s presentation will be followed by a panel discussion with industry professionals directly involved with developing and delivering new semiconductor products to the market.

Moderator: Daniel Nenni, SemiWiki

Panelists:

Doug McBane CEO, DGM Consulting

Fares Mubarak CEO, Spark Microsystems

Pete Rodriguez CEO, Silicon Catalyst

Aram Sarkissian VP & GM, Eurofins EAG

Rick Seger CEO, SigmaSense

U.K. Should Emulate Israel for Semiconductor Startups to Succeed

Reprinted from EETimes Europe / October 14, 2021 Nitin Dahad

Senior executives from the U.K. semiconductor industry met at Bletchley Park to discuss how to nurture and grow the country’s semiconductor startups.

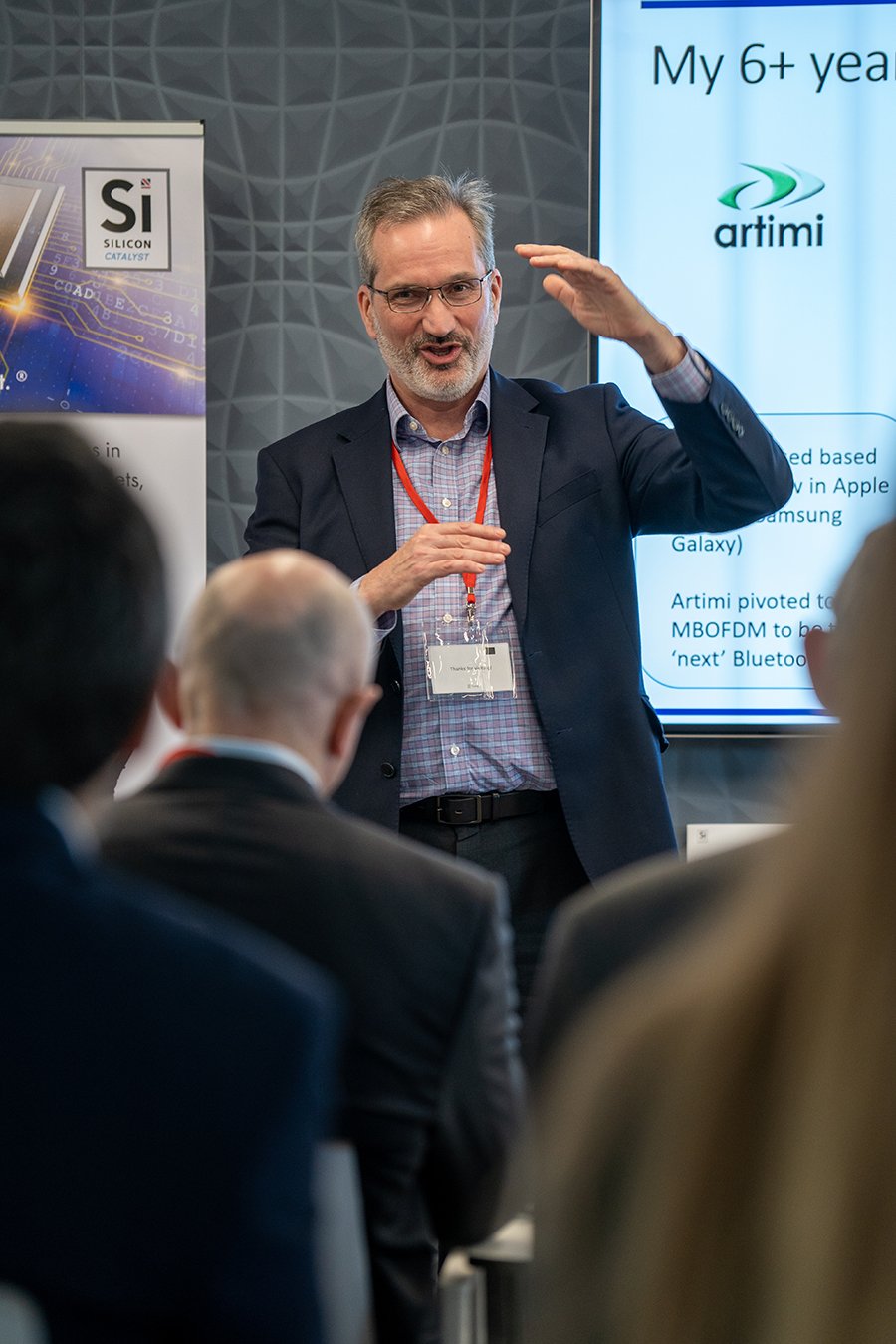

This week, some of the most successful senior executives from the U.K. semiconductor industry gathered at the birthplace of modern computing, the Bletchley Park National Museum of Computing, to discuss how to crack the code to chip startup innovation in the country.

It was rather like a re-run of Captain Ridley’s shooting party [see my note at the end of this story], quipped Sean Redmond, managing partner of the incubator Silicon Catalyst, co-host of the gathering this week with the National Microelectronics Institute (NMI). The two organizations announced a collaboration just a couple of weeks ago to work on creating the right environment for more U.K. semiconductor startups to be more successful globally.

Senior chip industry executives met at Bletchley Park to debate how to crack the code for U.K. semiconductor startup innovation and scaleup, appropriately in front of one of the code-breaking machines at the National Museum of Computing. (Image: Silicon Catalyst)

The gathering this week was aimed at bringing together in a room those who can potentially help make that happen, discuss what are the challenges and the possible solutions. There were successful chip and EDA industry veterans like Jalal Bagherli, Simon Davidmann, and Stan Boland, as well as other influencers in the ecosystem such as John Goodacre and Neil Dickens, plus of course various startup founders, as well as government representation on semiconductor industry policy.

The debates on challenges are for semiconductor startups in the country threw up some common themes, as we heard from two startups, Salience Labs and Cascoda, as well as the panel discussion that followed.

It won’t be anything new for those familiar with the U.K. scene over the last 20-25 years as it’s the same old story: lack of long-term capital for scaling up, access to talent, and the right kind of support from government programs. On the latter point, one panelist said many U.K. startups have to apply for DARPA funding in the U.S. or look for European Union grants, as there’s no real program for them in the U.K.

The CEO and co-founder of Salience Labs, Vaysh Kewada, talked about her experience as a new startup established in 2020, and how as part of the Silicon Catalyst program the company already raised its first funding in March 2021, and is about to close its second round of funding to build the company’s prototype chip. She highlighted the top three needs of a semiconductor startup as supply chain, customer integration, and hiring at speed. On the supply chain, she said being part of Silicon Catalyst helps, especially since their SoC is multi-platform. Customer integration is also essential as, she said, “We need to be able to show traction and demonstrate integration with a customer’s requirement, hence the need to work closely with customers.”

Vaysh Kewada, CEO and co-founder of Salience Labs, talks about their startup jouney as the company develops its high-speed photonics chip for AI acceleration, and the support it has from Silicon Catalyst. (Image: Nitin Dahad)

Salience Labs is developing a high-speed photonics chip for AI acceleration. The company has shown that photonic processors can process information much more rapidly and in parallel, something electronic chips are incapable of doing. Their work on this was published in the Nature journal earlier this year. Kewada said, “The market needs a new compute platform as a result of the end of Moore’s Law and with AI compute requirements doubling every three months. With the rise of silicon photonics, we have been able to come together as a team to create hybrid photonic in-memory compute. Photonics can enable us to get up to 50x improvement in inferences per second per watt compared to electronics.”

Meanwhile, Bruno Johnson, CEO of Cascoda, explained how his company played the long game having established the company in 2007 and without having the support of a dedicated chip industry support network as provided by Silicon Catalyst now. He talked about how Cascoda worked over many years to realize their vision of enabling standards-based IoT to address the huge lack of interoperability in the industry. It invented a new type of radio demodulator which offers a significant increase in range by improving receiver sensitivity, without sacrificing power consumption and with no need for a power amplifier. Johnson’s approach to growth is to work on developing a scalable technology that integrates into existing infrastructure, and work with or be part of standards bodies (he’s involved with the Thread Group as well as the Open Connectivity Foundation).

The panel: Where are we now, where do we want to go?

Having heard from the two startups, the panel dissected where is the U.K. semiconductor industry right now as regards nurturing startups, and where could the industry learn from.

The panel dissected where is the U.K. semiconductor industry right now as regards nurturing startups, and where the industry could learn from. (Image: Silicon Catalyst)

Tim Ramsdale, CEO of Agile Analog, a four-year old startup who recently closed a $19 million funding round, highlighted that the semiconductor industry is a long-term play, in the range of 20-30 years. “But in the U.K., the appetite for investing in semiconductors wasn’t really there, say five years ago. We also need larger ecosystem players here,” he commented, the latter point referring to the ability to get a wider skills and talent pool to enable hiring locally.

John Reilly, the sales director for silicon partners in EMEA, India and Russia for Arm, illustrated how Israel has managed to succeed with nurturing its chip startup ecosystem and how this could be a model for the U.K. “Our business in Israel is almost exclusively with startups. So what lessons can we learn? Well, if you look at the Israeli military, it churns out a pool of experienced resources [who then go on and do their own tech startups when they leave].” In addition, he said success breeds success. “This is when successful entrepreneurs go and help other startups and also become role models themselves.”

Reilly certainly has a key point. Two of Israel’s military units, unit 81 and unit 8200, have alumni who have launched many successful technology startups. Since they are elite units looking at things like security and intelligence, and whose remit is to use technology to develop solutions that keep Israel safe, they have excellent skills and experience of using technology to solve real world problems.

When they come out of the units, they already have teams that have worked together successfully so often come together to form their own startups – an example of a recent one is NeuroBlade, who just raised $83 million for its compute-in-memory chip. Hailo is another example. According to one report earlier this year, soldiers and officers who served in Unit 81 between 2003 and 2010 have since then founded many startups – in fact around 100 veterans from the unit at the time founded 50 companies and have raised over $4 billion, with valuations over $10 billion.

Coming back to the panel, Alec Vogt, director northern Europe for Synopsys, talked about the importance of an incubator like Silicon Catalyst for startups. “In the U.K., there is no lack of creative ideas. However, what happens next is not so great. Because there isn’t an appetite for longer term investment in semiconductors in the U.K., the ecosystem supporting semiconductor investments is weak, and there are no real government funding programs.” He then said that there was a danger of the country closing in on itself. “We need to be open, create a pool of talent, bring expertise and funding here so that the great ideas can have more chance of becoming a success.”

The Silicon Catalyst and NMI collaboration is meant to address some of the issues around access to various aspects of support, including tools and in-kind benefits from key partners of the network, plus access to funding sources.

Redmond said, “The UK has world class research universities and a track record for semiconductor innovation. It also has fifteen semiconductor fabs specializing in advanced processes for photonics, power and mixed-signal RF applications. This manufacturing base has been extended with a strong MEMS, PICs and ASIC ecosystem. Combining these local assets with international partners and entrepreneurial drive creates a springboard for semiconductor start-up success.” Hence, his vision was to help create a better support network for semiconductor startups to help them grow.

Meanwhile, the legal entity behind NMI, called TechWorks, was keen to work with Silicon Catalyst to ‘de-risk’ the path to growth for chip startups in the country. The CEO of TechWorks, Alan Banks, said, “By cultivating collaboration and ensuring government recognition of the semiconductor sector in areas such as automotive, IoT, communications, AI and edge computing, we have ambitions to facilitate the next generation of semiconductor companies building on the legacy of companies such as Arm, Wolfson, Icera and, more recently, Graphcore.”

Note: “Captain Ridley’s shooting party” was the cover name used by secret service agents from MI6 and intelligence experts who headed out to Bletchley Park in 1938 to activate the secret base that became the home of the code breaking center, where Alan Turing and many others broke a number of German codes, including that of the Enigma machine.

Fall 2021 Advisor Event

Malcolm Penn, CEO of Future Horizons, was the invited speaker at our Fall Advisor Event on Oct 20, 2021.

The link above is the recording of his presentation with his spot on insights on the supply chain challenges of the semiconductor industry as well the critical importance of marketing for startups.

Great introduction by Sean Redmond, Managing Partner of SiliconCatalyst.UK.

2021 Silicon Catalyst Webinar

"Maximizing Exit Valuations for Technology Companies"

Wednesday July 28, 2021

11:30

Introductions

11:40 - 11:55

Pete Rodriguez - M&A Advice

11:55 - 1pm

Panel Session discussion, with Q&A from attendees

Silicon Catalyst and Harvest Management Partners, a leading global investment banking firm providing unique M&A services for technology companies, are pleased to invite you to our joint webinar, “Maximizing Exit Valuations for Technology Companies”.

The webinar will kick-off with a short presentation by Pete Rodriquez, CEO of Silicon Catalyst, detailing his deep experience with mergers and acquisitions, from both sides of the table. Pete’s presentation will be followed by a panel session discussion with CEO’s reviewing their exit stories, and will be joined on the panel by investment professionals.

Topics to be discussed during the webinar:

Key elements needed for a strategic exit - both technology & business aspects

Product differentiation and scarcity of technology

Preparation and strategy for an exit

Timing, timing & timing

Selecting and hiring the right banker/advisor

Orchestrating a competitive process

See press coverage of the acquisitions of Omnitek (Intel) and Lumerical (Ansys)

Moderator

Pete Rodriguez, CEO Silicon Catalyst

Pete Rodriguez has over 35 years of experience in the Semiconductor industry. Pete is currently CEO of Silicon Catalyst www.siliconcatalyst.com and on the board of Hysai, advisory board of Harvest Management Partners and an observer on the boards of Mentium Technologies, Espre Technologies and Owl AI. Pete was formerly VP & GM of Interface and Power at NXP Semiconductors. Prior to NXP Pete was CEO of Exar Corporation, CEO of Xpedion Design Systems, Chief Marketing Officer at Virage Logic, Major Account Manager at LSI Logic and Program Manager at Aerojet Electronic Systems. He spent twelve years as an entrepreneur with three different startups and has raised over $30 Million in venture capital. He retired from the US Naval Reserves with the rank of Commander. Pete has served on public, private, advisory and non-profit boards of directors. He is a graduate in strategy and policy of the Naval War College. Pete has an MBA from Pepperdine University, an MSEE from Cal Poly Pomona, and a BS in Chemical Engineering from the California Institute of Technology.

Webinar Panelists

Managing Director, Harvest Management Partners

Alain Labat is Managing Director of Harvest Management Partners (HMP), www.harvestmp.com a global boutique technology investment bank that he co-founded 11 years ago. He has focused HMP on M&A transactions and advisory for the semiconductor ecosystem in the private technology sector, selling some of his clients to industry giants such as Ansys, Cadence, Intel, Synopsys and Siemens to name a few. He has also worked on the advisory side with Fiat Chrysler Automotive, TE Connectivity and SirusXM.

Prior to HMP, Alain was President and CEO of VaST Systems Technology, which was acquired by Synopsys (SNPS) in February of 2010. His other important roles leading up to VaST include; Co-founder, President and CEO of Sequence Designs, which is now a part of ANSYS (ANSS) and Senior Vice President of Worldwide Sales and Marketing at Synopsys. Aside from his management roles, Alain has also been an Entrepreneurial Partner at Menlo Ventures for their Semiconductor/EDA practice. Alain has a diploma from INSEEC, France and an MBA in international management and marketing from Thunderbird, The School of Global Management in Glendale, Arizona.

Warren Lazarow, Firmwide Co-Chairman of O’Melveny’s Corporate Department, is nationally and internationally recognized as one of the market’s leading advisors to technology-focused companies and investors. Warren primarily focuses his practice on the corporate representation of public and private technology companies, venture capital and private equity firms, and investment banks. He is a boardroom-level advisor who frequently serves as outside general counsel, helping management teams, boards of directors, and investors shape and execute their business strategies, and providing experienced counsel on legal issues ranging from day-to-day corporate and regulatory matters to high-stakes strategic matters. Over the course of his career, Warren has handled more than 200 M&A transactions ranging from US$1 million to US$10 billion; more than 100 public offerings of equity, debt, and convertible securities, raising more than US$2.6 billion; and more than 1,000 private financings spanning initial seed financings, venture capital financings, growth capital financings, private equity financings, and recapitalizations.

Warren has been chosen four times for inclusion on Forbes Magazine’s prestigious “Midas List” of the technology industry’s Top 100 Dealmakers Worldwide.

Investment Principal Robert Bosch Venture Capital

Yvonne Lutsch is an Investment Principal at Robert Bosch Venture Capital’s (RBVC) affiliate office located in Sunnyvale, responsible for sourcing, evaluating and executing investments for RBVC in the USA and Canada in deep tech fields like Artificial Intelligence, Industrial IoT, Mobility, Quantum Computing, or Sensors. Prior to this position, Yvonne was Director of Technology Scouting and Business Development for Bosch Automotive Electronics in North America. Her team’s focus was to identify startups, disruptive technologies, or business opportunities with the potential to create significant value to Bosch. Prior to that, Yvonne held different leadership positions in Quality Management, Operations, and Engineering in Automotive and Consumer Electronics within Bosch Germany. Yvonne received a diploma in Experimental Physics from the University of Siegen, Germany, and holds a Ph.D. in Applied Physics from the University of Tuebingen, Germany.

ex-CEO of Lumerical, acquired by Ansys

James Pond was a co-founder and CTO of Lumerical and was a driving force behind the company’s core software algorithms, technology, and advanced photonic modeling capabilities. He has two decades of experience in optical and photonic simulation, and is the author of numerous papers, patents and conference presentations. Currently he is Principal Product Manager at Ansys where he works on integrating Lumerical technology into the Ansys portfolio. He has a PhD in Physics from the University of British Columbia, Canada, and a DEA and Magistère in Physics from l’Université Paris-Sud (Orsay) and l'Ecole Normale Supérieure in France.

ex-CEO of Omnitek, acquired by Intel